The Department of Urban and Inner-City Studies continues to seek ways to decolonize post-secondary education.

Santos describes the processes of decolonization to include: “student access to the university, access to university career (Indigenous faculty); research and teaching contents; disciplines of knowledge, curricular, and syllabi; teaching/learning methods; institutional structure and university governance; and relations between the university and society at large.1 ” Although we agree with Santos that decolonization requires attention to all of these areas, we focus on creating spaces for learning that better align with decolonized learning, as well as developing courses that integrate Indigenous wasy of knowing, and where possible, infused with Indigenous voices. The History of Indigenous Resistance and Development in Winnipeg: 1960-2000 is an example of a course that continues to evolve in the spirit of decolonizing pedagogy.

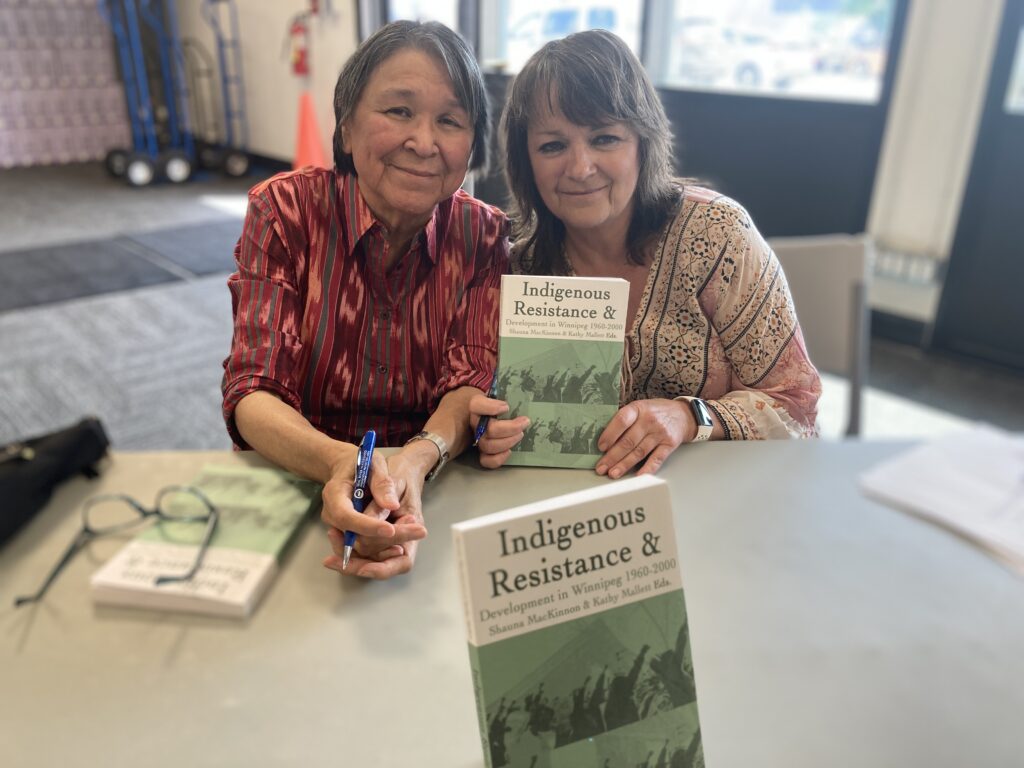

The course was jointly developed with Kathy Mallett, an Indigenous women and long-time inner-city activist. When Kathy and I found it near impossible to find content written by Indigenous people, we compiled an edited collection that featured the voices of Indigenous people gathered through the Indigenous Archives Project, which Kathy led through the the Manitoba Research Alliance2

In addition to our book, we continue to experiment with multiple tools and have not confined learning to the classroom. Some of the activists that students are learning about participate in panel discussions in the classroom. Others have since passed away or moved away but students get to meet them through their videorecorded interviews. Student have visited the Neeginan Centre to learn about its history from one of its founders. They visit the Archives at the University of Manitoba and learn from archivists how to access the Indigenous Archives Project materials that are stored there. We continue to work with the UM Archives to broaden accessibility to the collection through digitization. We are always looking for new means of sharing hundreds of hours of recorded interviews. For example, when John Loxley, the MRAs long time principal investigator passed away just as we began to compile the book for the course, he was posthumously awarded a SSHRC Impact award for his work with the Manitoba Research Alliance. We were able to use the financial award to further develop teaching tools for the course. The result was the creation of two topic-specific audio productions featuring the voices of Indigenous activists featured in the book. These productions are now a central feature of the course and we are seeking ways to make them available to a broader public. We believe this to be in keeping with Smith’s assertion that “knowledge sharing” between Indigenous people is an integral part of decolonizing research. We believe that it is our responsibility to ensure that the recorded oral histories of Winnipeg based Indigenous activists are shared broadly. Knowledge mobilization—or sharing as Smith describes it— is not optional for us, nor is it only for academic audiences.

Place matters

Kathy and I also believe that place matters. The continued oppression of Indigenous people in Canada and in the spatialized marginalized inner-city neighbourhoods in Winnipeg calls for a localized critical pedagogy that aims to facilitate processes and create safe spaces for students to make sense of their realities within their “specific historical, political and social context”. 3 The Department of Urban and Inner-City Studies (UICS) is a small university department in the Faculty of Arts. Although the University of Winnipeg made clear its mandate to “indigenize” in 2015, the Department of UICS has been on this path since relocating to the North End in 2011. We have developed a pedagogical framework that melds decolonizing content with critical-placed based pedagogies.

We welcome all students, but we prioritize Indigenous students and others who have been excluded from the university, supporting them to shed their internal doubts, heal from trauma, explore what is possible, build confidence and embrace the idea that acquiring a university degree is achievable. Our experience has shown that bringing critical pedagogies into inner-city, colonized spaces can have a transformative impact on the lives of students from all walks of life.

At the end of the fall 2024 term, students were asked to reflect on the course. One student said: “I really liked how you used archived interviews to teach us and brought people into our class to talk to us about their personal experiences. Instead of just giving lectures about people and places you brought them to us and took us to those places to give us experiences which have been super impactful.” One student learned from the guest appearance of an Indigenous leader featured in the book that her grandmother had once served as a board member of the Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre. She expressed feeling very proud to learn this. Another student who grew up in the neighbourhood shared that he was proud to have learned about the many Indigenous leaders in his community.

We have learned a thing or two after offering this course for the second term. We know that we are on the right track, but there is more that we can do to further develop our decolonized approach and Kathy and I will continue to explore new methods moving forward on this challenging but worthwhile journey.

- Boaventura de Sousa Santos and Maria Paula Meneses (Eds.). Knowledges Born in the Struggle. Constructing the Epistemologies of the Global South. New York: Routledge. 2020, 221 ↩︎

- Mackinnon, S. and Mallett, K. 2023. History of Indigenous Resistance and Development in Winnipeg. 1960-2000. Winnipeg: ARP. ↩︎

- Shauna MacKinnon. Critical place-based pedagogy in an inner-city university department: truth, reconciliation and neoliberal austerity. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 29(1), 2019: 137–154. ↩︎